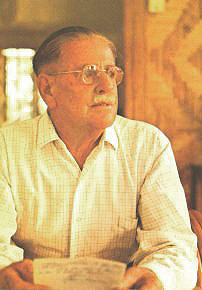

Commander Eric Feldt, OBE, RAN

Shortly after World War 1, the Naval Staff instituted a system of civilian coast- watchers, whose duty it was to report any matters of naval intelligence coming to their notice. Slowly the scheme was developed until the settled part of the Australian coast was under observation. In the late twenties, the organization was extended to Papua, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

On the mainland of Australia, land-line telegraphy was depended on for the transmission of messages, but in the islands it was necessary to use radio. The principal stations were controlled by Amalgamated Wireless of Australia (AWA) and later teleradios (editor's note: radio transmitter/receivers) communicated to them. However. the area was but sketchily covered, radio stations being placed to suit commercial development and without regard to strategic needs.

Soon after the outbreak of war in 1939, the writer was appointed Staff Officer (Intelligence) at Port Moresby and given the task of expanding the coast-watching organization to meet war needs, but still on an unpaid civilian basis.

New Guinea, the Bismark Archipelago, the Solomons and the New Hebrides form a screen across the north-east of Australia. The object was to make this a sensitive web which would immediately give notice of any hostile force penetrating it. The peace-time organization left gaps, so that it was rather like a fence with a few gates in it left open.

I had lived in New Guinea for sixteen years as a civil servant and had served in most districts. In addition, I had made friends in Papua and the Solomons, so that I not only knew the country but knew the people in it and many of them knew me. I made my first survey, with the assistance of the local governments, using any means of transport available and making personal contact with all those placed in strategic positions. Throughout, personal contact was of greater importance than the official relationship.

To complete the chain of stations, the Naval Board agreed to supply teleradios on loan to those most likely to see any hostile ships or aircraft, on the condition that the person to whom the teleradio was lent would report any item of intelligence value. Each was instructed in his duties and was given a code in which to make the reports. Later all were exercised by "dummy runs". By August 1942 there were over a hundred teleradios tied in, each to its own centre, either Port Moresby, Rabaul, Tulagi or Vila, on a special frequency which was rarely used so that attention would not be called to it. During this time a teleradio reporting system had been organized along the same lines in the islands of Torres Strait.

Until the entry of Japan into the war, the Coastwatchers remained a civilian, static, defensive reporting system, designed to report the incursions of an enemy into our own territory. The question of Coastwatchers remaining in the event of the country being overrun had been raised. It was decided against, except in the case of naval intelligence officers.

The entry of Japan into the war left the island screen as the front line. Coast-watchers reported scouting enemy aircraft and, soon afterwards, enemy flights on their way to bomb Rabaul. Tabar Island lay directly on their route and Page, the Coastwatcher there, usually gave Rabaul twenty minutes warning of an attack. On occasions when the aircraft passed beyond his sight, others reported them. So that Rabaul had no raid without a warning, which minimised casualties, though there were no effective aircraft there to meet the attacks. On 23 January 1942, a Japanese force occupied Rabaul, driving our troops, a little more than a battalion in strength, into the jungle of New Britain. With them went the naval staff of Rabaul, and the silence closed about them.

So I sent a signal to McCarthy, who was Assistant District Officer at Talasea, about two hundred miles west of Rabaul, on the north coast of New Britain. He was a civilian and not under my orders and quite free to save himself. I asked him to take his teleradio and go towards Rabaul to find out what was the fate of our forces. Two planters volunteered to assist him; he took one with him and left the other to manage the base. Travelling by launch, he met the first refugees at Pondo and was joined by other civilian helpers there, one of whom walked across New Britain to advise anyone on that side to join McCarthy. The latter went farther forward, sending back the small bodies of soldiers he found at plantations.

In the meantime a few small vessels had been collected on the New Guinea coast and these came across Vida Strait to assist in the evacuation. McCarthy sent his parties westward, and was met by the good news that a small motor vessel was still hidden at Witu Island. He took possession of her, loaded his men, over two hundred, on board and ran out to China Strait and safety. Several of the civilians who had assisted him remained behind to continue reporting.

His signals had told us that there was still a large number of troops on the south coast of New Britain so the Laurabada, in charge of Lieutenant Ivan Champion, RANVR, was sent across to pick them up. She made her arrival at dawn, remained at anchor camouflaged by branches during daylight, and then successfully ran back in the night with another hundred and fifty men.

Page, on Tabar, remained on his island. as did Kyle and Benham in southern New Ireland, the latter two sending off two boatloads of escapees while themselves remaining. Woodroffe, on Anir, was raided and his teleradio smashed, though he himself escaped to the jungle. All of these were captured and killed a few months later. Cecil Mason who landed from a submarine in an attempt to rescue them, shared their fate.

In Papua, New Guinea and the Solomons most civilians were evacuated. Many Coastwatchers, however, decided to remain and continue their reporting. They were still civilians, were unpaid, and had no provision for their families. Their only hope of survival appeared to be in the reconquest of the country by our forces, which was problematical in the dark days of 1942. Theirs was a very special type of courage.

In the Solomons, the Resident Commissioner abandoned the north-western part of the group, but kept his staff in the south-eastern islands - himself retreating to Malaita. In Bougainville, Assistant District Officer Read, moved supplies inland and prevailed upon the small section of the AIF (ed: the Australian Army) there to do likewise. Mason, a planter, also made preparations to stay.

In February the Japanese occupied Lae and Salamaua, but this move had been foreseen and Vial, an Assistant District Officer, was commissioned into the RAAF (ed: Royal Australian Air Force) and sent into the jungle. From a ridge near Salamaua, he watched every Jap movement and, for six months, gave warning by teleradio of every Japanese attack on Port Moresby. These warnings were invaluable. Eventually, Japanese penetration forced the relinquishment of the post, but by that time many additional spotter stations had been established in Papua so that Port Moresby did not go unwarned.

In March the Japanese occupied Buka Passage and the Shortland Islands. Read had already taken to the jungle, but Good, on Buka, was killed by the Japanese, an incautious news broadcast being a contributing factor.

The death of Good brought the question of the status of the Coastwatchers to a head. Those in the field were soon given rank or rating.

Shortly after this, General MacArthur assumed the supreme command in the South-West Pacific and it was decided that the Coastwatchers, with analogous organizations, should be placed under GHQ's direct command as the Allied Intelligence Bureau.

Plans at this time envisaged an early attack on Rabaul and the Coastwatchers were given the task of landing parties to make a preliminary scout survey of the position. To observe native reaction to the Japanese invasion, Wright was landed from a submarine about forty miles from Rabaul. He stayed ashore for a week and was then picked up. His information indicated that we would have no insuperable difficulties to overcome from the indigenous population, so we prepared a small motor vessel for the trip. However, the Jap beat us to the punch by landing at Buna. The task was then given us to buoy and light the channel from Milne Bay to Oro Bay, and this was successfully done, Ivan Champion acting as pilot for the first vessels through*.

* Lionel Veale's story of such a mission is included in this chapter on the Coastwatchers.

Those Coastwatchers who had remained after McCarthy had brought out troops from Rabaul were concentrated at Saidor on the New Guinea coast. Supplies were dropped to them from aircraft. They collected stores, teleradios and launches and were held in readiness for the future.

The Japs moved down into the Solomons. Their first ships were reported by Kennedy. American naval forces attacked them, developing into the Battle of the Coral Sea. In spite of their losses, (the Japanese) occupied Tulagi and soon after, commenced constructing an airfield on Guadalcanal. There were four coast watchers on Guadalcanal - Macfarlan, the NIO (ed: Naval Intelligence Officer), Clemens, the District Officer, Rhoades, a planter, and Schroeder, a trader. There were also a few miners who assisted. These kept watch on the Japanese developments, sending natives right into the camp and reporting the progress the Japs were making.

The Japanese also extended their holdings from the Shortlands to Buin (ed: on the south coast of Bougainville) which soon became a major base. Mason moved down to overlook it, and gave a daily tally of Japanese shipping in the harbour. Read continued to watch Buka Passage. The Japs sent patrols out after them, but these gave up after a day or two, and the Coastwatchers returned to their posts and continued reporting.

Thus it was that, before the American attack on Tulagi and Guadalcanal, the Japanese positions were under observation and the strength of his forces known, while the routes he would use for counter-attack and reinforcement were also under surveillance. The nearest enemy air bases were at Rabaul and Kavieng, and aircraft from these would fly over Bougainville on their way to Guadalcanal and would be seen and reported by our men.

The American carriers were tied in to our frequency so that they could receive warnings without delay. The warnings themselves were in plain language and there were alternative channels in case the direct reception was poor.

The attack achieved perfect surprise. Tulagi and Guadalcanal were taken within hours and transports moved in to discharge. Then came a signal from Mason on Bougainville stating that twenty-four torpedo bombers were on the way. This gave two hours warning, allowing ships to prepare to meet the attack. Transports were got under way, and destroyers were disposed with their guns at the ready, so that the aircraft ran into a trap, all but one being shot down.

Next day, Read gave warning of forty-five dive bombers (ed: in fact, they were 27 twin engine "Betty" torpedo bombers with Zero escorts), which were met by carrier-borne fighters. The attack was broken up with heavy casualties to the Jap and only one ship was hit. For the next few days, warnings preceded each attack, resulting in such high Japanese losses that there was a lull until further air forces could be flown in.

The warnings from Bougainville had been vital. After the first week it became necessary to withdraw the carriers to avoid submarine attack, leaving the beachhead without air defence. Had the air attacks been unheralded, they must have achieved considerable success and would have continued after air cover had been withdrawn, so that the position could not have been built up to stand the serious counter-attacks which later developed.

A week after the landing on Guadalcanal, Mackenzie (who had been NIO at Rabaul when it was captured) and Train established themselves near the airfield. Soon afterwards, Henderson Field became operative and American Grumman fighters were flown in. By this time the Japanese had made good their losses and the air attacks recommenced. Mackenzie received the warnings and passed them on, so that again there were fighters in the sky to meet the bombers.

In spite of their losses, the Japanese air attacks continued and the base was sometimes shelled at night, while troops were landed to retake it. During this time the Coastwatchers on Guadalcanal came in to the base, fortunately without casualties.

Australian

Coastwatcher Paul Mason on Bougainville played a key role in the successful

US Marine landing

on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942. His early warnings of Japanese bombers approaching

Guadalcanal enabled

the Americans to prepare appropriate anti-aircraft defences.

The Japanese counter-attack culminated in November when a large convoy set out, preceded by a force which included battleships, to land troops on Guadalcanal. The concentration of shipping and its movement had been observed by the Coastwatchers on Bougainville, so that forces were ready to meet the attack, which was defeated with heavy losses.

Buin had by this time become the base from which shipping and aircraft moved against Guadalcanal, so, as Mason could not see all that went on, measures were taken to cover it. Two Coastwatchers were landed by submarine on Vella Lavella and two on Choiseul. These had a perfect view of all that went past. Soon afterwards, the Japanese established a base at Munda where Kennedy's native scouts kept them under observation, and another Coastwatcher was inserted on Rendova Island, where he had a perfect view of Munda airfield and harbour from a mountain.

During this time the Buna campaign was being fought in New Guinea. Parties kept watch there on the coast between Buna and Salamaua, calling up aircraft to attack barges and landing parties so that the Japanese supply was utterly disorganised.

Plans were in train at this time to attack Salamaua and Lae as soon as Buna fell. To provide air warnings to cover this operation, parties were required on New Britain along the routes which would be followed by the enemy aircraft. The Coastwatchers from Saidor were dispatched to carry out this duty. However, the Japanese occupied many of the points selected before Buna fell, and four Coast- watchers were killed and the rest driven back to Saidor. When Buna fell, the troops were so exhausted by the campaign that they were not fit for further operations, so no attack was made until months later.

Fit personnel were sent in to relieve the survivors of the New Britain operation. Two of the latter were killed while returning, and the relief party itself was shortly driven out. Another party, which had been overlooking Finschafen, was also forced to retire, and a third landed on the Sepik River to observe Wewak* had to retreat as well. In all these cases men were fired at from a few yards and had miraculous escapes, purely due to the poor marksmanship of the Japs. My own health failed, and Commander J. C. McManus took over the command.

The section of AIF on Bougainville was also relieved by submarine at this time. They had done little of positive value, but had been a force which had discouraged Japanese patrols. Three additional Coastwatchers were landed to assist Read and Mason, the latter having been driven away from Buin. Many civilians, including missionaries, were evacuated at the same time.

A further party, led by Wright, was landed on New Britain to keep watch on the barges and submarines running supplies from Rabaul to Lae.

In the Solomons, Coastwatchers led reconnaissance parties to Munda and Rendova, scouting the ground which was to be attacked. A further post was established on Kolombangara, overlooking the airfield there. By this time, when aircraft set out to attack Guadalcanal, they were reported by post after post, so that we probably had a more accurate estimated time of arrival than the Japs did themselves. Hardly a barge moved without being reported and strafed.

A subsidiary operation, which developed into one of importance, was the rescue of shot down airmen. Throughout the Solomons, the natives were loyal and helpful and would lead any American airman to the nearest post, where he was cared for until he could be sent out by the aircraft or launch which brought in supplies. Japanese airmen were killed by the natives. Later, the survivors of U.S.S. Helena were cared for on Vella Lavella, all being sent out safely, though there were numerous Japanese posts on the island.

On Bougainville, however, the Japanese decided to liquidate the Coastwatchers. Thousands of troops must have been employed on the operation. They scoured the country, intimidated the natives, and succeeded in driving the Coastwatchers from their posts, until evacuation became imperative. This was carried out by submarine, after the loss of eight killed or made prisoners. Read and Mason had been on the island for seventeen months.

In June 1943, the advance against the Japanese commenced. In each case, Coastwatchers landed with the troops and set up a station to receive warnings of air attacks, while others guided the troops through the jungle. Just before the Torokina landings, (Coastwatcher) parties were again landed on Bougainville, while reinforcements expanded the New Britain Coastwatchers until there were five separate parties operating there.

Others landed at Long and Rooke islands to see what the Japs there would do in reaction to the Cape Gloucester and Arawe landings, while other parties operated in the Sepik Valley.

A party landed at Hollandia, but it met with disaster. Its leader and four others being killed in action when their presence was discovered by the enemy.

With the move forward beyond New Guinea, the enemy forces in the latter area became impotent except in defence, and coastwatching, in the sense of obtaining intelligence, came to an end. However, activities did not. Many natives had served with the Coastwatchers and more could be easily obtained. These were armed and used in guerrilla operations. This had been done to a limited extent in the Solomons in the early days, but now it became the principal occupation. In New Britain, Japs retreating from Cape Gloucester to Rabaul were ambushed and their small posts were wiped out until the guerrillas actually held the island south of the Gazelle Peninsula, so that our troops landed and built their base at Palmalmal unopposed.

On Bougainville, four parties were continuously operating behind the enemy lines. They spotted air targets and carried out a war of attrition in which they inflicted more casualties on the Japs than did the Australian troops on the island.

The success of the Coastwatchers was largely due to the experience of the personnel. Nearly all were men who had lived in the country, who knew it and the natives, and who felt at home in it. It is easier to teach a man how to operate a teleradio or shoot a submachine gun than to teach him how to live in the jungle. The men, experienced and actually known to the natives, gained their help, for it would be impossible to conduct such operations if the natives favoured the enemy.

Throughout, we had ready co-operation from other Services. Aircraft dropped supplies to parties and sometimes picked them up; submarines and PT boats (ed: patrol torpedo boats) landed them and took them off, always with a readiness and helpfulness which cannot be obtained by merely ordering an operation to be carried out. Without this co-operation, the Coastwatchers would have been gravely handicapped.

Lastly, there was help from the enemy. He was so stupid that he did not realise the damage that was being done to him and many times neglected to take measures against us, and, by his own actions, alienated native sympathy. In fact, he was invaluable.

Eric Feldt, RAN

First published in "As you were!" (1946)