WHAT WAS THE BATTLE FOR AUSTRALIA 1942-43?

Text and Web-site by James Bowen. Last updated 15 August 2020.

"The fall of Singapore can only be described as Australia’s Dunkirk…The fall of Dunkirk initiated the Battle for Britain. The fall of Singapore opens the Battle for Australia."

The Honourable John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, (press release dated 16 February 1942).

Senshi Sosho, the official Japanese history of the Pacific War 1941-45, provides the following evidence of Japan's hostile plans for Australia in 1942:

"The

pressing issue of strengthening policies was discussed at the Imperial Headquarters-Government

Liaison

Conference on 10 January 1942...With regards to Australia (including

New Zealand), the following was determined:

Proceed

with the Southern Operations, all the while blockading supply from Britain and

the United States and strengthening the

pressure on Australia, ultimately with the aim to force Australia to be freed

from the shackles of Britain and the United States." (1)

Extract from Senshi Sosho courtesy of the Australian War Memorial

and the Australia Japan Research Project.

Japan brings death

and destruction to the tranquil beauty of Sydney Harbour. The Australian Navy

barracks ship,

HMAS Kuttabul lies on the bed of Sydney Harbour after a Japanese midget

submarine attack in 1942.

| "As a graduate historian, with a special focus on Japanese history and the Pacific War, it fell to me to define the concept and scope of a Battle for Australia, and to write a paper that justified commemoration of a Battle for Australia in 1942. At private meetings during 1997, Major General James and I defined the concept of a Battle for Australia to describe the clash of Japanese and American strategic war aims with Australia as their focus that produced a series of great battles in 1942 across the northern approaches to Australia, including the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Kokoda Campaign, and Guadalcanal Campaign. In this context, the Battle for Australia was to be viewed as a lengthy and bloody struggle to prevent the Japanese achieving their strategic Pacific War aims of controlling Australia, and preventing the United States aiding Australia and using Australia as a base for launching a counter-offensive against the Japanese military advance. For their part, the Americans were determined to protect their access to Australia and its New Guinea territories in 1942, even at the risk of their five precious fleet carriers that had survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor." Extract from text below. |

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Works of reference and notes can be found at the end of this chapter .

The Battle for Australia does not refer to invasion planning by the Japanese Navy in 1942

The Battle for Australia does not refer to planning in early 1942 by the Imperial Japanese Navy to invade the Australian mainland. At an Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 7 March 1942, the Navy General Staff and Navy Ministry agreed to their limited invasion of Australia plan being deferred in favour of the Army's preferred Operation FS. This change of strategy towards Australia is explained below in the paragraphs headed " Invasion of Australia deferred on 7 March 1942 in favour of pressure on Australia to surrender by implementing Operation FS".

Formal observance of Battle for Australia Day

In June 2008, the Rudd Government initiated formal observance of Battle for Australia Day on the first Wednesday of September of each year. When the RSL* took the initiative in 1998 to commemorate a Battle for Australia, it was viewed in the historical context of a massive struggle throughout 1942 and early 1943 to defeat Japan's strategic plan to isolate and control Australia by means of a master plan bearing the code reference Operation FS.** In forming a conclusion that the defence of Australia against Japanese military aggression in 1942 could fairly be described as a "Battle for Australia", the Victorian Branch of the RSL drew not only from sources such as the official Australian World War II Histories but also from sources that were not available to those who wrote the relevant Australian histories in the 1950s, including the massive official Japanese history of the Pacific War, called Senshi Sosho (translated as "War History Series") and the published historical works of distinguished Japan scholars, including Professor Henry Frei and Professor John J. Stephan.

* RSL is an abbreviation for Australia's largest veterans' organization The Returned & Services League of Australia. ** "FS" is an abbreviation for Fiji-Samoa.

Control of access to Australia considered a vital strategic aim by the Japanese and Americans in 1942

It was the distinguished Japan scholar and historian Professor Henry Frei* who drew our attention to the fact that the major Japanese offensive against Australia and the United States that began with the Battle of the Coral Sea (7-8 May 1942) was intended to implement Operation FS and had two purposes. The first was to sever Australia's lines of communication with the United States, and thereby, deny the Americans access to Australia as a base from which they could launch a counter-offensive against Japan. The second purpose was to deny American support to Australia and place intense military pressure on Australia by blockade and psychological warfare to abandon the Allied cause and surrender to Japan.(2) See also the quote from Senshi Sosho above the photograph of Sydney Harbour in 1942. At the time of the Battle of the Coral Sea, Australia had already ignored two demands for its surrender made by Japanese Prime Minister General Hideki Tojo in the Diet (Japanese parliament) in January and February 1942.(3) A detailed treatment of Imperial Japan's hostile plans for Australia can be found on this web-site in the chapters commencing "The Japanese planned to compel Australia's surrender in 1942".

* Author of the definitive work on Japan's hostile plans for Australia in 1942 "Japan's Southward Advance and Australia" (1991) Melbourne University Press.

The US Navy strategy

in the South-West Pacific in 1942 was primarily directed to preventing the Japanese

occupying Australia, its New Guinea mainland territories, and the British Solomon

Islands (including Guadalcanal) in order to preserve them as bases from which the United States and

Australia could launch joint counter-offensives against Japan.** Control of access to Australia was considered vital by both the Japanese and

Americans in 1942, and both were determined to prevent the enemy gaining that

access.** The Battle

of the Coral Sea was initiated by the Japanese in early May 1942 to gain

control of Australia by implementing Operation FS. The Kokoda

Campaign was initiated by the Japanese in July 1942 to seize Port Moresby and gain control of Australia

by implementing the revised Operation FS, now known as Operation MO. On 7 August

1942, the US Navy initiated the Guadalcanal Campaign to block Japanese control of the British Solomon Islands which would threaten

American lines of communication with Australia.

** Richard B. Frank provides an excellent account of US Navy and Japanese Navy

South Pacific strategies in 1942 in his magisterial work Guadalcanal,

(1990) Random House at pages 1-32.

Author's Note In this brief explanation of the Battle for Australia, any quotations from Senshi Sosho, the 102 volume official history of Japan's involvement in World War II, are drawn from the translations provided by Dr Steve Bullard, Senior Historian at the Australian War Memorial. The translated text of the relevant parts of Senshi Sosho that deal with Japan's hostile plans for Australia in 1942, including the Japanese master plan Operation FS (see below), is available on the web-site of the Australian War Memorial. The translated text can be downloaded as a PDF file, and all references to that text on this web-site are to numbered pages of the PDF file. Dr Bullard's important contribution to Australia's Pacific War history and the cooperation of the Australia-Japan Research Project in providing access to these translations are acknowledged with deep appreciation. Unless otherwise expressly stated, all references to "Professor Frei" or "Frei" are to the distinguished Japan scholar and historian Professor Henry Frei and his authoritative work "Japan's Southward Advance and Australia"(1991). |

JAPANESE PLANNING TO COMPEL AUSTRALIA'S SUBMISSION TO JAPAN IN 1942

Japanese planning before Pearl Harbor to seize Australia's New Guinea Territories

The First Operational

Stage of Japan's campaign of military conquest in the Pacific began with the devastating surprise attack on the American Pacific Fleet naval base at Pearl

Harbor on 7 December 1941 and had initially been intended to halt short of the large island of New Guinea.(4) The islands of New Britain and New Ireland in Australia's Territory of New Guinea League Mandate* were included in the First Operational Stage at the behest of Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue who was commander of the

4th Fleet, or South Seas Force, based at Truk in Japan's Caroline Islands League

Mandate.* Inoue warned the Japanese

Navy General Staff that Japan would face grave danger if the Americans

were allowed to establish bases in Australia and its New Guinea Territories

for their inevitable counter-offensive. This would allow the Americans to outflank Japan's eastern defensive perimeter anchored on the Marshall group of islands. He urged an offensive against Australia

and the British Solomons (including Guadalcanal) to counter this danger. Imperial Headquarters agreed with Inoue that the two largest islands of Australia's Territory of New Guinea (New Britain and New Ireland) should be added to his list of Pacific Ocean targets in the First Operational Stage that already included Guam and Wake islands in the northern Pacific.(5) For a detailed treatment of this hostile Japanese planning directed against Australia, see the chapter "Before

Pearl Harbor, Japan targets Australia's New Guinea Territories".

* Australia and Japan were given responsibility to administer these former German colonies by the League of Nations at the end of World War I.

Vice Admiral Inoue persuades Navy General Staff of the need for Japan to capture Australia's Port Moresby and the British Solomons

Although he had only been authorised to capture the islands of New Britain and New Ireland in Australia's Territory of New Guinea Mandate in the First Operational Stage, Vice Admiral Inoue appreciated that a major Japanese base planned for Rabaul on New Britain would be vulnerable to attack by Allied bombers based at Lae and Salamaua on the northern New Guinea mainland, at Port Moresby on the southern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua, and on islands comprising the British Solomon Islands chain (including Tulagi and Guadalcanal). Inoue urged Navy General Staff to extend Japan's southern defensive perimeter by capturing Port Moresby in Australia's Territory of Papua and Tulagi in the British Solomon Islands.

Note: Although it appears to be not well known, Australia exercised full sovereignty over its Territory of Papua in 1942. Papua was never a League of Nations Mandate. It had been transferred by Britain to Australian ownership in 1906. Port Moresby was the capital of Papua in 1942, and a landing of Japanese troops in Papua to capture Port Moresby would constitute an invasion of Australia under international law.

Inoue's argument for the capture of Australia's Port Moresby was greatly strengthened by the quick Australian response to the capture of Rabaul on 23 January 1942. The Royal Australian Air Force immediately began to bomb Japanese shipping and installations at Rabaul from airstrips at Port Moresby, Lae, and Salamaua. On 29 January 1942, Japan's Navy General Staff responded positively to Vice Admiral Inoue's arguments by ordering the Commander in Chief of Japan's Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, to capture Lae, Salamaua, and Port Moresby on the New Guinea mainland, and Tulagi island in the British Solomon Islands chain.(6) A detailed treatment of Japanese planning for invasion of Australia's New Guinea territories can be found in the chapter "Before Pearl Harbor, Japan targets Australia's New Guinea Territories".

Japanese planning to pressure Australia into surrender to Japan in 1942 by means of Operation FS

To counter the perceived threat from Australia as an American ally in 1942, the admirals of Japan's Navy General Staff and Navy Ministry had resolved as early as December 1941 that key areas of the northern Australian mainland should be occupied in order to deny the Americans access to Australia as a base for a counter-offensive and to isolate Australia from American and British aid. To invade and occupy those key areas of the Australian mainland, the Japanese Navy required army troops and the admirals requested three Japanese Army divisions for that purpose.(7)

The generals of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff, and the Prime Minister of Japan, General Hideki Tojo, appreciated that Australia posed a serious threat to Japan while it remained an ally of the United States.(8) The generals were willing to provide troops to seize and occupy Australia's two New Guinea Territories in 1942 but they believed invasion and occupation of the vast Australian mainland would place an impossible manpower and logistical burden on the Japanese Army at that time.(9)(10) The request by the Japanese Navy for troops for an invasion of northern coastal areas of the Australian mainland was rejected by the generals at a meeting of the Army and Navy Sections of Japan's Imperial Headquarters on 27 February 1942. The generals felt that their army resources had already been heavily overextended by Japan's rapid and massive territorial conquests, and that the Japanese Army needed time to consolidate its territorial gains. The generals had a different but equally sinister plan for bringing Australia under Japanese control.*

* See reference to the views of Army Chief General Hajime Sugiyama at Footnote 9.

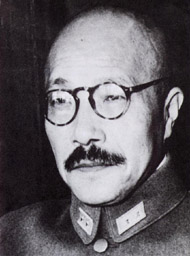

![]()

Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo opposed the Japanese Navy plan to invade northern coastal areas of the Australian mainland. Tojo believed that Australia could be compelled to submit to Japan without need for invasion by

measures such as intensified blockade and psychological warfare that were components of Operation FS. The Curtin government poster was thought alarmist by some in 1942 who were unaware of Japan's sinister plans for Australia.

Japan's Prime Minister General Hideki Tojo and his generals believed that severing Australia's lifeline to the United States, together with an intensified blockade and psychological warfare, would act as a Japanese noose to "throttle Australia into submission" to Japan. This Japanese strategic war plan directed against Australia and the United States had been given the code reference "Operation FS" (also known as "FS Operation").(11) Senshi Sosho, the official Japanese history of the Pacific War, makes it clear that Japanese pressure on Australia was intended to force submission to Japan:

"The pressing issue of strengthening policies was discussed at the Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 10 January 1942...With regards to Australia (including New Zealand), the following was determined: Proceed with the Southern Operations, all the while blockading supply from Britain and the United States and strengthening the pressure on Australia, ultimately with the aim to force Australia to be freed from the shackles of Britain and the United States."(12)

Professor Frei tells us that, after its anticipated surrender to Japan in 1942, General Tojo was planning to incorporate Australia as a puppet state into Japan's compliant political bloc called the New Order in Greater East Asia and its equally compliant economic bloc called The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. For more information about these Japanese plans for Australia in 1942, see the chapter: "Japan's hostile plans for Australia after surrender?".

Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 28 February 1942 approves implementation of Operation FS

The Japanese Army had pushed Operation FS at the Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 10 January 1942 to deflect the Japanese Navy plan to invade the Australian mainland.(13) Another Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 28 February 1942 approved implementation of Operation FS, and the formal document concluded that "total isolation of Australia was the key to Japan's mastery of the South-West Pacific...to isolate Australia, the strategically valuable islands of New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) had to be occupied".(14) Ceylon was shortly afterwards dropped from the agenda at the behest of Japan's Combined Fleet.(15)

Invasion of Australia deferred on 7 March 1942 in favour of pressure on Australia to surrender by implementing Operation FS

By 4 March 1942, the Japanese Navy had agreed with the Army that severing Australia's lifeline to the United States and pressuring Australia into full submission to Japan by means of Operation FS were more important objectives than the invasion and occupation of coastal areas of the northern Australian mainland that the Navy had earlier proposed. At the Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference on 7 March 1942, the Navy General Staff and Navy Ministry agreed to their plan for limited invasion of Australia being deferred in favour of the Army's preferred Operation FS. Planning for an invasion of the Australian mainland was not totally dropped at this Liaison Conference. It was agreed that planning for invasion of the Australian mainland would be referred back to Navy and Army headquarters for further study. On 11 March 1942, an Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference formally ratified implementation of Operation FS in a document entitled: "Fundamental Outline of Recommendations for Future War Leadership".This document was presented by Japan's most senior military officers General Sugiyama and Admiral Nagano to Emperor Hirohito on 13 March 1942 who approved it as commander-in-chief of Japan's military. (16)

The strategic aim of Operation FS was to extend Japan's southern defensive perimeter from Port Moresby in the Australian Territory of Papua to Fiji and Samoa in the South Pacific. Port Moresby, Fiji, and the islands between them (the British Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal, New Hebrides, and New Caledonia), would be heavily fortified by Japan and equipped with forward air and naval bases. The waters between each island fortress in this chain would be guarded by the Japanese Navy. A tightly enforced Japanese blockade would sever Australia's lifeline to the United States and prevent military support (including troops, munitions, equipment, oil, metals, and rubber) reaching Australia from the United States and Britain. Behind a barrier of captured and fortified Japanese island bases, it was intended that Australia would be blockaded and pounded into submission to Japan. See Frei at page 172. A detailed treatment of Imperial Japan's hostile plans for Australia can be found in the chapters commencing "The Japanese planned to compel Australia's surrender in 1942".

Operation FS would be anchored on Port Moresby which belonged to Australia in 1942. The capture of Port Moresby was of vital importance to Imperial Japan's military leaders. Port Moresby was situated on the southern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua and separated from the Australian mainland by a 500 kilometre (310 mile) stretch of the Coral Sea. Its capture would deny the Allies a forward base from which to launch air attacks on Japan's newly acquired military bases in the Australian Territory of New Guinea League Mandate, and in particular, the major Japanese base at Rabaul. With the whole of the island of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands under Japanese control, Japan could establish forward air and naval bases on these captured territories from which it could strike deeply into the Australian mainland and intercept military support for Australia from the United States. Port Moresby would also provide Japan with a potential springboard for an invasion of the Australian mainland.

BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA

The great American carrier USS Lexington ("The Lady Lex") has received fatal damage in the defence of Australia in the

Battle of the Coral Sea. 216 dead crew members accompanied their ship on her last journey to the floor of the Coral Sea.

The Battle

of the Coral Sea (7–8 May 1942) resulted from Japan's first attempt to capture Port Moresby by a powerful seaborne invasion force. Although part of the broader Operation FS, the capture of Port Moresby was assigned the specific code reference Operation MO. A smaller operation undertaken at the same time as the Port Moresby operation was the capture of the island of Tulagi in the British Solomons on 3 May 1942. The Japanese intended to establish a forward seaplane base at Tulagi which was only defended by a very small Australian force. After first capturing Tulagi, the Japanese moved their invasion transports towards Port Moresby under the protection of one light carrier Shoho and two large fleet carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku. It was intended that the two Japanese fleet carriers would guard the invasion force against intervention by American carriers and, after doing so, proceed south to attack military targets on the Australian mainland.

Forewarned by American and British code-breakers of this Japanese plan to capture Port Moresby, a combined American and Australian naval force prepared to intercept the Japanese invasion fleet. While an Australian-American cruiser squadron stood off the southern tip of Papua to block the movement of the invasion transports through the Jomard Passage and towards Port Moresby, the American fleet carriers Lexington and Yorktown sank the escorting Japanese light carrier Shoho on 7 May 1942. On the following day, 8 May, the American carriers engaged the two Japanese fleet carriers in the Coral Sea. Lexington was hit by two air-launched torpedoes, and caught fire and sank after the battle. Yorktown was hit by one bomb that exploded deep inside the carrier and caused serious damage. Although Yorktown was still operational, Rear Admiral Fletcher decided to withdraw his carrier group from the Coral Sea but not the Australian-American cruiser squadron which remained off the coast of Papua until 10 May to block any possible attempt by a Japanese invasion force to reach Port Moresby.

Battle damage inflicted on the two Japanese fleet carriers forced their withdrawal from the Coral Sea. With the Australian-American cruiser squadron still blocking the approach to Port Moresby, and no carriers left to cover the landing at Port Moresby, the Japanese felt compelled to withdraw their Port Moresby invasion force to their base at Rabaul. The Japanese decision to withdraw their invasion force was partly influenced by air reconnaissance which mistakenly identified the Australian-American cruiser squadron as comprising "one carrier, one battleship, two heavy cruisers, and nine destroyers".[reference needed]

The Allied strategic victory over the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea preserved Port Moresby as the main Allied forward base on the island of New Guinea; it denied the Japanese their anchor for Operation FS; it denied the Japanese the Coral Sea as a barrier to protect their captured bases on the island of New Guinea; and it denied the Japanese a base from which their bombers could range as far as 1,600 km (1,000 miles) into the Australian mainland and across the Coral Sea. Another very important aspect of this naval battle was the damage caused to the Japanese fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. That damage prevented their participation in the crucial Battle of Midway in early June 1942 where their presence could have changed the course of that battle significantly. Although Japan had experienced a major strategic defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea, Prime Minister Hideki Tojo told the Japanese Diet on 28 May 1942 that it was not too late for Australia to submit to Japan. Frei at p. 172. A detailed treatment of the Battle of the Coral Sea can be viewed on this web-site.

BATTLE OF MIDWAY

The Battle of Midway (4-6 June 1942) must be mentioned in any comprehensive treatment of the Battle for Australia because Midway changed the strategic situation in the Pacific dramatically, and affected the course of the Battle for Australia profoundly.

"THE FAMOUS FOUR MINUTES" by R.G. Smith

This superb painting by a master of aviation painting, the late R.G. SMITH, depicts one of the defining moments of the Pacific War when the tide turned against the Japanese aggressors at America's Midway Islands. Lieutenant Richard Best and his two wingmen in their Douglas Dauntless SBD dive-bombers have just launched a successful attack on the Japanese flagship aircraft carrier Akagi. The crushing defeat inflicted on the Imperial Japanese Navy by the very much smaller United States Pacific Fleet at Midway put an end to Japan's ambition to dominate the central and western Pacific regions, and deprived Japan of the capability to threaten Australia into surrender to Japan

Isolation and control of Australia by means of Operation FS were Japan's top strategic priorities in the Pacific until the Doolittle carrier raid on Japan (18 April 1942) caused equal strategic priority to be given to the total destruction of the US Pacific Fleet.(17) Shamed by the failure of the Japanese Navy to protect Japan and the emperor from an American carrier raid on 18 April, the Commander in Chief of Japan's Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, intended to destroy the carriers of the US Pacific Fleet by attacking America's Midway Atoll in the central Pacific. When the American carriers arrived to defend Midway Atoll, Yamamoto intended to finish the destruction of the US Pacific Fleet that he had begun at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Yamamoto was not aware that the Americans had broken Japan's naval code JN25 and were aware of the trap that he was setting at Midway. When the powerful Japanese carrier strike force arrived off Midway Atoll at first light on 4 June 1942, it was the Japanese carriers that were ambushed by the American carriers.

In the Battle of Midway (4–6 June 1942), Japan's four best fleet carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu were sunk. This massive defeat at Midway removed Japan's earlier naval superiority over the US Pacific Fleet, and lifted the threat to Australia's coastal cities and towns from Japan's powerful carrier force. A detailed treatment of the Battle of Midway (4-6 June 1942) can be viewed on this web-site.

Accepting that Japan no longer possessed the ability to project naval power across the Pacific as far as Fiji and Samoa, Imperial Headquarters cancelled Operation FS on 11 July 1942.(18) However, the strategic objectives behind Operation FS were not cancelled, andSenshi Sosho records that, despite cancellation of Operation FS, at Imperial Headquarters:

"There were great expectations for the proposal that the FS Operation would be undertaken after December 1942."(19)

The loss by Japan of four great fleet carriers at the Battle of Midway would compel an overland attempt by the Japanese to capture Port Moresby and initiate the Kokoda Campaign.

New Japanese strategic plans directed against Australia following the defeat at Midway

After the disastrous naval defeat at Midway, Japan's Imperial Headquarters still believed that Japan's top strategic priority in the Pacific must be to sever Australia's lifeline to the United States and deny the United States access to Australia as the springboard for a counter-offensive. The cancellation of the ambitious Operation FS was not intended to reduce the pressure on Australia to surrender to Japan. Less ambitious plans than Operation FS were developed to achieve those objects. The Japanese Navy General Staff authorized Operation SN to strengthen Japan's outer defensive perimeter by constructing advanced airbases at key strategic locations in Australia's Territory of Papua, including the Louisiade Islands (off the eastern tip of Papua), and the British Solomon Islands to the east of New Guinea.(20) Aerial reconnaissance of Allied staging bases on New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and Fiji continued from the Japanese airbase at Tulagi in the British Solomons. On 13 June 1942, Navy General Staff authorised construction of an airbase at Lunga Point on the northern coast of Guadalcanal.(21) A 48 km (30 mile) stretch of sea separated the Japanese seaplane base at Tulagi from Lunga Point. On 29 June 1942, about two thousand Japanese troops and workers landed at Lunga Point where they began construction of a strategically vital airfield (later to be known famously as Henderson Field). When completed, this forward airbase would enable Japanese bombers to range far across the Coral Sea and bomb the Allied staging bases on New Hebrides and New Caledonia. This Japanese threat to lines of communication with Australia caused deep concern to the Commander in Chief United States Navy, Admiral Ernest J. King, who believed that the United States needed to preserve access to Australia as a major base for an American counter-offensive to recover the Philippines from Japanese occupation. Admiral King resolved to make the Japanese stay on Guadalcanal a brief one.

The capture of Port

Moresby and Guadalcanal were to be the initial

stages of revised Japanese strategic operations against Australia that no longer

extended further east than the British Solomons. The capture of Port Moresby and Guadalcanal would enable the Japanese

to intensify dramatically their existing blockade of Australia which was mostly based on submarine attacks on shipping. Longer range

air bombing of the Australian mainland could be undertaken from Port Moresby*,

increased submarine attacks on Australian coastal cities and shipping could

be launched from Port Moresby, and Japanese medium bombers based on Guadalcanal could

strike more effectively at Australia's vital shipping lifeline to the United

States.*

* The Japanese medium bombers Mitsubishi G3M (Allied code name "Nell") and Mitsubishi G4M (code name "Betty") both possessed operational bombing ranges of at least 1,000 miles or 1,609 kilometres and could strike deeply into the northern Australian mainland and strike at Allied staging bases on New Hebrides and New Caledonia. (22)

THE KOKODA CAMPAIGN

Returning from the Battle of Isurava, soldiers of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion trudge through deep mud on the hellish Kokoda Track.

In heavy fighting

under

appalling

conditions,

these young heroes have played

a vital role at Kokoda, Deniki, and Isurava in blunting the momentum of the Japanese advance towards Australia. AWM 013288.

Recognising that the Japanese Navy had been seriously weakened by the Midway defeat, and that a seaborne attack on Port Moresby was no longer feasible, Imperial General Headquarters suspended Operation MO and assigned the capture of Port Moresby to Japan's 17th Army commanded by Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake with the Navy adopting only a supportive role.(23) An aerial survey of the topography between the northern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua and Port Moresby persuaded the Japanese high command that it might be possible to capture Port Moresby by an overland attack using a track across the rugged Owen Stanley Range which separated the northern and southern coastal plains of Papua. Studying maps in Tokyo, the task may have appeared deceptively easy to the army planners. The distance in a straight line from Buna and Gona on the northern coast of Papua to Port Moresby on the southern coast was only about 160 kilometres (100 miles) but to reach Port Moresby Japanese troops would have to cross some of the world's most rugged and unforgiving terrain. General Hyakutake was ordered to examine the feasibility of an overland attack on Port Moresby (the RI Operation Study).(24) For the purposes of this study, the Yokoyama Advance Force, commanded by engineer Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama, and supported by one infantry battalion from the elite Nankai Shitai (South Deas Detachment), would land at Buna and Gona on the northern coast of Papua and assess the feasibility of capturing Port Moresby by crossing the Owen Stanley Range. The infantry battalion would quickly capture Kokoda and secure the northernmost ridge of the Owen Stanleys.(25) The engineers would convert the Japanese beachheads at Gona and Buna into a massive linked and heavily fortified base capable of supporting a much larger force. Yokoyama was required to assess and report to 17th Army on the the feasibility of moving an army across the Owen Stanleys to Port Moresby by the beginning of August.(26)

Intelligence warnings alert General MacArthur to the need to defend Kokoda

The American Supreme Commander South-West Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur had been warned by American naval intelligence in Melbourne (FRUMEL) in early June 1942 that the Japanese were likely to attempt an overland attack on Port Moresby. The potential threat to the strategically important Kokoda airstrip on the northern slopes of the Owen Stanleys could not be ignored. On 24 June, the army commander at Port Moresby Major General Morris ordered militia troops of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion to cross the Owen Stanleys with the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) and secure Kokoda. The PIB was a force of about 280 native soldiers led by 30 Australian officers and NCOs. Neither Australian battalion would carry heavy weapons. The ruggedness of the terrain and narrowness of the Kokoda Track required the soldiers to move for most of the arduous trek in single file, and companies would move in stages to reduce serious supply problems while on the track. The first company of the 39th Battalion to move into the Owen Stanleys on 8 July 1942 was B Company, numbering about 100 officers and men in three platoons. C Company would follow on 23 July.

B Company of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion reaches Kokoda

By 15 July, B Company troops had reached Kokoda. Their commander Captain Sam Templeton left one platoon to defend Kokoda and then set out with two of his platoons to patrol towards Buna on the northern coast. The commander of the PIB Major Watson split his battalion with about half patrolling between Kokoda and Awala, a small village located about half way between Kokoda and Buna/Gona, and the other half patrolling a large area north-west of Buna.

Australia was invaded by Japan on 21 July 1942

On 21 July 1942, Australia was invaded by Japan when about 2,000 troops of the Yokoyama Advance Force landed at Gona and Buna on the northern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua. The Tsukamoto Battalion, drawn from the Nankai Shitai's 144th Infantry Regiment and supported by a company of the elite 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), immediately moved inland to capture Kokoda with its important airstrip and clear a path to the Kokoda Track for the rest of the Nankai Shitai if Colonel Yokoyama deemed it feasible for a Japanese army to reach Port Moresby by crossing the Owen Stanley Range. The landing of these Japanese invaders opened the Kokoda Campaign which would be fought entirely on Australian soil.*

*To understand why the Kokoda Campaign was fought on Australian soil, it is necessary to appreciate the distinction between the Japanese invasion of Rabaul on 23 January 1942 and the Japanese landings in Papua on 21 July 1942. The Japanese landing at Rabaul was not an invasion of Australian soil because the Australian troops were defending a mandate granted to Australia by the League of Nations in 1920 for administrative purposes only. The landings in Papua were an invasion of Australia because the Territory of Papua belonged to Australia in 1942. Papua was never a League of Nations mandate. Britain transferred full ownership of Papua to Australia in 1906 and that ownership conferred on Australia full sovereign rights over Papua. Australia retained full ownership of Papua until 1975 when the Territory was granted independence, and combined with the former New Guinea League Mandate to form Papua New Guinea.

Australians stage a fighting withdrawal to Kokoda

When news of the Japanese invasion of Papua reached Port Moresby, General Morris ordered the commander of the 39th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Owen, to fly to Kokoda on 23 July to command the 39th Battalion and the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) which were now designated Maroubra Force.The first contact between the Australians and the Tsukamoto Force occurred on 23 July near Awala. A lightly armed forward PIB patrol engaged the advancing Japanese but was quickly routed when the Japanese responded with mortar, heavy machine guns, and artillery. Aware that they were facing a formidable Japanese force that greatly outnumbered them and had heavier weapons, the only option available to the Australian force was a fighting withdrawal to Kokoda. Captain Templeton was killed during this fighting withdrawal.

Japanese high command resolves to implement a two-pronged attack on Port Moresby

During the days following the Japanese landings in Papua, Colonel Yokoyama reported his belief that a Japanese army could reach Port Moresby by means of the Kokoda Track. Responding to this news, Imperial Headquarters ordered Lieutenant General Hyakutake on 28 July to prepare for an overland attack on Port Moresby which was reinstated as Operation MO and a simultaneous attack on the Allied airbase at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua (Operation RE). The rest of the Nankai Shitai, supported by the 41st Infantry Regiment (Yazawa Force), would deploy to Papua and follow the Tsukamoto Force to the Kokoda Track. Major General Tomitaro Horii would command his own Nankai Shitai and the 41st Infantry Regiment for the attack on Port Moresby. The Japanese high command envisaged that Horii's force would emerge from the Kokoda Track and be supported in its attack on Port Moresby by Japanese aircraft flying from the captured Allied base at Milne bay.

Japanese capture Kokoda on 29 July 1942

With a mixed force of about eighty militia troops of the 39th Battalion and a small number of native troops of the PIB, Lieutenant Colonel Owen prepared to defend Kokoda and its vital airstrip. He contacted Port Moresby by radio on 28 July and requested reinforcements and mortars. During the day two transport aircraft loaded with Australian troops and mortars circled the airstrip and then departed to the astonishment of the defenders. After nightfall on 28 July, hundreds of assault troops from the Tsukamoto Force swarmed over the Kokoda plateau. The Australians were quickly overwhelmed and Kokoda was captured in the early hours of 29 July 1942. Owen was killed in the attack and Australian survivors escaped through the Kokoda rubber plantation to Deniki.

39th Battalion recaptures Kokoda and loses it again

In the week following the Japanese capture of Kokoda, more companies of the 39th Battalion arrived at Deniki, and the new commander, Major Allan Cameron, decided to stage a counter-attack to recapture Kokoda. The counter-attack proved to be a disaster for the 39th Battalion. C and D Companies met overwhelming opposition and the Japanese pursued them aggressively back to Deniki. Captain Symington's A Company reached and captured Kokoda, but was forced to withdraw on 10 August after very heavy fighting.

Nankai Shitai arrives in Papua

With Kokoda now firmly under Japanese control, and the Kokoda Track now appearing to be open for the passage of a Japanese army, the main body of the Nankai Shitai embarked at Rabaul for Buna on 17 August 1942. The Nankai Shitai was closely followed by two battalions of the Yazawa Force which landed at Buna on 21 August. The continuing Japanese troop build-up in the Gona-Buna-Kokoda triangle had now reached 13,500 troops, and 10,000 of these were tough, jungle-trained combat veterans. From these troops, Major General Horii could draw a well-balanced fighting group which included six infantry battalions, mountain artillery, and engineers, for the overland attack on Port Moresby.

Battle of Isurava

At Deniki, Major Cameron's 39th Battalion now comprised only E Company and the exhausted and depleted C and D Companies. The Japanese attacked in strength on 13 August and on the following day, when the Japanese were pushing into the Australian positions, Cameron felt obliged to withdraw the remnant of his battalion to the village of Isurava on the first ridge above the northern foothills.

The men of the 39th Battalion dug in at Isurava. They were buoyed by the arrival of their new commander Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner on 16 August. His orders were to hold Isurava until relieved by veteran AIF units of the 21st Brigade which were then preparing to move up the Kokoda Track from Port Moresby. Honner found his men starving and in poor shape. He quickly set to work building up morale and deploying his depleted battalion as effectively as possible. He knew that if the Japanese broke through quickly at Isurava they would catch the AIF battalions at a grave disadvantage while strung out along the Kokoda Track. If this happened, it was likely that the Japanese would achieve the momentum that would enable them to reach Port Moresby.

Major General Horii launched his attack on Isurava on 26 August. This attack was timed to coincide with an attack on the Allied airbase at Milne Bay which was the second prong of the Japanese attack on Port Moresby. Outnumbered by at least ten to one at Isurava, the Australian militia troops stood firm. By mid-afternoon on that day, companies of AIF veterans of the 2/14 Battalion began arriving to relieve the 39th Battalion. Although suffering acutely from battle fatigue and starvation, the 39th Battalion declined to be relieved and stayed at Isurava to support the 2/14th Battalion as a reserve force.

In the great battle that took place at Isurava over four days from 26 to 29 August 1942 the Australians withstood repeated Japanese human wave attacks supported by mortar bombardment and mountain artillery. Major General Horii knew that the Australians were heavily outnumbered and he was prepared to sacrifice a large number of his troops to overrun the Australian defensive positions. By sheer weight of numbers, the Japanese finally penetrated the Australian lines and occupied the vital high ground on the western side of the Australian defensive perimeter. From this high ground, the Japanese were able to rake the Australian defenders with heavy machine gun fire. The commander of the 2/14th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Keys, realised that the position of the Australians at Isurava had become untenable in the face of overwhelming enemy numbers and the loss of the western high ground. Keys sought and received permission to withdraw from Isurava and set up a new defensive position further down the Kokoda Track.

Japanese defeat at Milne Bay

At Milne Bay the Australians and Americans had been developing a forward airbase since June 1942. Capture of Milne Bay would have provided the Japanese with an airstrip from which Major General Horii's attack on Port Moresby could be supported by Japanese aircraft when his troops emerged from the southern end of the Kokoda Track.

Timed to coincide with the Japanese attack at Isurava, on the night of 25–26 August 1942 the second stage of the overland Japanese offensive against Port Moresby was launched when 2,400 naval infantry, including the elite 5th Kure SNLF and the 5th Sasebo SNLF (Special Naval Landing Force) were landed at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua in heavy rain. The Japanese light tanks were quickly bogged in the deep mud. After ten days of very heavy fighting, and hampered by heavy rain, mud, and communication difficulties, Australian troops and aircraft forced the Japanese invaders to withdraw on 5 September 1942. For the first time in World War II, a Japanese invasion force had been driven back into the sea.

Major General Hori's drive towards Port Moresby defeated by a stubborn Australian fighting withdrawal

Despite being forced to withdraw, the Australian defence of Isurava had sown the seeds of Major General Horii's ultimate defeat. Although continuing to suffer very heavy losses, the Australians staged a fighting withdrawal lasting almost four weeks across the Owen Stanleys from Isurava to Imita Ridge on the mountains overlooking Port Moresby. At Ioribaiwa, on 25 September 1942, the Japanese drive towards Port Moresby finally ran out of steam. In their fierce determination to overcome the Australians, the Japanese had sustained nearly 3,000 battle casualties on the Kokoda Track. With Horii's supply lines in chaos, and his troops starving and exhausted, Japan's Imperial Headquarters acknowledged defeat on the Kokoda Track. Horii was ordered to withdraw his battered army to the Japanese beachheads at Gona-Buna. A savage war of attrition between the Americans and Japanese over possession of the strategic island of Guadalcanal in the British Solomons had deprived the Japanese of the capacity to reinforce Horii's troops for the final 40 km (25 mile) push to Port Moresby.

Strategic significance of Isurava

Between 26 and 30 August 1942, several hundred Australian soldiers defended the Kokoda Track at Isurava against 5,000 of Japan's best combat troops. The Australians were heavily outnumbered, inadequately armed, and poorly supplied, but their resolute stand over those four days at Isurava inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese and blunted the momentum of Major General Horii's drive towards Port Moresby. The stubborn resistance of the Australian troops at Isurava wrecked the Japanese timetable for crossing the Kokoda Track, gave time for Australian AIF reinforcements to be brought up, and laid the foundation for the ultimate defeat of Horii’s army before it could reach Port Moresby.

Battle of the Beachheads - Gona, Buna and Sanananda

In the mistaken belief that General Horii’s retreating troops were beaten, and that only a couple of thousand starving and exhausted survivors of the Kokoda Track would have reached the Japanese beachheads on the northern coast of Papua, General MacArthur ordered an assault by Australian and American troops on the Japanese beachheads stretching from the village of Gona to the neighbouring village of Buna. However, the Japanese had turned the beachhead villages into heavily fortified strongholds and had poured in thousands of fresh troops. MacArthur's terrible mistake produced a very heavy cost in Australian and American lives. With the sea on one side, and protected by swamp and jungle on the landward side, nine thousand fanatical Japanese troops had prepared a killing ground for the advancing Australian and American troops. From their camouflaged bunkers and sniper positions, the Japanese took a heavy toll on the Australians and Americans over the two months of savage fighting in appalling conditions that were necessary to capture the Japanese beachheads and expel the invaders from the Territory of Papua.

The Cost of the Kokoda Campaign

This invasion of Australian sovereign territory ended when the Japanese were defeated in Papua on 22 January 1943 after six months of some of the bloodiest and most difficult land fighting of the Pacific War. Australia lost 2,165 troops killed and 3,533 wounded. The United States lost 671 troops killed and 2,172 wounded. The heroism of heavily outnumbered young Australian soldiers on the Kokoda Track and at Milne Bay saved Australia from an invasion of its own territory and a grave Japanese threat to the mainland. A detailed treatment of the Kokoda Campaign can be viewed on the linked Pacific War web-site.

THE GUADALCANAL CAMPAIGN

The Guadalcanal Campaign extended from 7 August 1941 to 7 February 1943, and included seven naval battles and major land battles. The defeat of the Japanese on Guadalcanal deprived Japan of the eastern anchor for their plan to isolate and blockade Australia into submission. The Guadalcanal Campaign is too complex to be included here but an overview of the Guadalcanal Campaign is provided on the linked Pacific War web-site.

ORIGIN OF THE MODERN CONCEPT OF A BATTLE FOR AUSTRALIA

The modern concept of a Battle for Australia owes its origin to a private letter dated 24 July 1997 that I wrote to the National President of the Returned & Services League of Australia (RSL), Major General W. B. Digger James, AC, MBE, MC. I was then Honorary Counsel and a State Executive member of the Victorian RSL.

The choice of "Battle for Australia" to describe the bloody struggle to deny Japan control of Australia

Major General James and I chose to use the term "Battle for Australia" to describe the clash of strategic war aims with Australia as their focus that produced Coral Sea, Kokoda, and Guadalcanal. That descriptive term was also used in deference to Australia’s wartime Prime Minister, John Curtin, who first used the term "Battle for Australia" in reference to the expected struggle for survival facing Australia after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. See the chapter "He was coming South - to compel Australia's surrender to Japan".

As a graduate historian, with a special focus on Japanese history and the Pacific War, it fell to me to define the concept and scope of a Battle for Australia, and to write a paper that justified commemoration of a Battle for Australia in 1942. In doing so, I drew heavily on the works of distinguished Japan scholars and historians such as Professor Henry Frei and Professor John J. Stephan.* At private meetings during 1997, Major General James and I defined the concept of a Battle for Australia to describe the clash of Japanese and American strategic war aims with Australia as their focus that produced a series of great battles in 1942 across the northern approaches to Australia, including the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Kokoda Campaign, and Guadalcanal Campaign. In this context, the Battle for Australia was to be viewed as a lengthy and bloody struggle to prevent the Japanese achieving their strategic Pacific War aims of controlling Australia, and preventing the United States aiding Australia and using Australia as a base for launching a counter-offensive against the Japanese military advance. For their part, the Americans were determined to protect their access to Australia and its New Guinea territories in 1942, even at the risk of their five precious fleet carriers that had survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

This modern concept saw the Battle for Australia beginning on 28 February 1942 when an Imperial Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference approved implementation of Operation FS as a means to produce Australia's submission to Japan by isolation from American aid, intensified blockade, and psychological warfare. The first military action of the Battle for Australia occurred when the Japanese implemented Operation FS by initiating the Battle of the Coral Sea (7-8 May 1942). It can be fairly argued that the threat to Australia from "intensified blockade" was lifted when the Japanese lost their anchor points for such a blockade at Port Moresaby and Guadalcanal. This happened when the Japanese were ousted from Papua on 22 January 1943 and Guadalcanal on 7 February 1943. After 7 February 1943, the Japanese adopted a defensive posture with a view to retaining their hold on captured territory in Australia's New Guinea Mandate and the British Solomons. Although this concept of a Battle for Australia has its beginning in Japan on 28 February 1942 and ending with the expulsion of the Japanese from Guadalcanal on 7 February 1943, it would deny the Battle for Australia a meaningful context in the Pacific War if its treatment did not begin with mention of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and end with the Battle of the Bismark Sea (2-5 March 1943) which destroyed Japan's capability of waging anything but a defensive war against Australia.

* Professor of Japanese History at the University of Hawaii

In defining the scope of the Battle for Australia, we were assisted by discussion with the internationally respected Australian military historian, Dr David Horner (now Professor Horner).

We felt that a national commemoration in the first week of September of each year was desirable to honour the service and sacrifices of those who defended Australia at its time of greatest peril. We wanted the commemoration to include schoolchildren and the countries that aided the defence of Australia in 1942, and these features were incorporated in our proposal to commemorate a Battle for Australia. These features would also be incorporated into the Order of Service for the first commemoration of the Battle for Australia held at the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne in September 1999.

When Major General James and I were satisfied that we had defined appropriately the concept and scope of a Battle for Australia, and provided the justification for commemorating that battle, I wrote the paper that proposed commemoration of a Battle for Australia in 1942 and submitted it to Mr Bruce Ruxton, AM, OBE, President of the Victorian Branch of the RSL. The proposal was endorsed and strongly supported by Mr Ruxton who took it to the National Congress of the RSL in 1998 where it was approved that the first Wednesday in September of each year be set aside for commemoration of a Battle for Australia.

Formation of a Battle for Australia Commemoration Council

The paper approved by the RSL provided the foundation for national commemoration of a Battle for Australia when it was accepted at the inaugural meeting of the Battle for Australia Commemoration Council on 14 August 1998. The council included representatives from major Australian veterans' organizations.

Alternative versions of a Battle for Australia

Since the RSL acted in 1998, it has become apparent that other versions of a Battle for Australia are being promoted. These other versions include a battle that lasts until Japan's surrender in 1945; a battle that fails to link Coral Sea, Kokoda and Guadalcanal as components of a Japanese strategic master plan to control Australia (and of course, Operation FS was such a plan); and a battle that makes no reference to the critical role that was to be played by Japanese-occupied Guadalcanal in isolating Australia from American help. In regard to Guadalcanal, it is important for Australians to remember that the cruiser HMAS Canberra was lost in the Guadalcanal campaign on 9 August 1942, and that Australian coastwatchers serving at great risk to their lives in the Japanese occupied Solomon Islands provided vital early warnings of Japanese air strikes on the highly vulnerable American transports when they were unloading US Marines, supplies, and equipment on the beaches of Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The formal observance of Battle for Australia Day on the first Wednesday of September of each year as a day of national commemoration suggests to me a need for those who support commemoration of the Battle for Australia to endeavour to be consistent in defining its concept and scope if that is possible. I feel that this consistency may be assisted by me explaining how the RSL came to approve commemoration of a Battle for Australia and what it saw as the rationale for such a commemoration.

Challenges to the concept of a Battle for Australia have been shown to lack credible historical foundation

It is necessary to mention that the historical concept of a Battle for Australia in 1942 has not gone entirely unchallenged. Although the Japanese official history of the Pacific War Senshi Sosho admits the existence of Operation FS, and treats its hostile plans for Australia in considerable detail, it has been suggested that there was no Japanese master plan to produce Australia's submission to Japan in 1942. Senshi Sosho does not make for easy reading, but that is no excuse for denial of its clear evidence of a grave Japanese threat to Australia in 1942 from Operation FS.

It has been suggested that if there had been a Battle for Australia in 1942, it would have been mentioned in the official Australian histories of WWII. This flimsy argument ignores the fact that the modern concept of a Battle for Australia draws heavily on translations of Japanese historical sources that were not available to those who wrote the official histories in the 1950s. Those Japanese sources make it clear that that the great battles across the northern approaches to Australia in 1942, including Coral Sea, Kokoda, and Guadalcanal, arose from a clash of Japanese and American strategic aims that had control of Australia as their focus.

There has been denial from some quarters that there was any Japanese planning at high military levels to invade Australia in 1942 and denial that any invasion of Australia actually occurred in 1942. Senshi Sosho makes it clear that invasion of the Australian mainland reached the highest levels of the Japanese Navy before it was replaced by adoption of Operation FS. Although these challenges were not supported by references to credible historical evidence, they achieved some recognition in those sections of the media that thrive on controversy rather than fact. It appears to have escaped the notice of those raising these challenges that the whole of the Kokoda Campaign was fought on Australian soil to expel Japanese invaders. See paragraph above headed "Australia was invaded by Japan on 21 July 1942". Planning at Japan's Imperial Headquarters for the invasion of Australian territory that led to the Kokoda Campaign is covered above in the paragraphs beginning "Japanese planning before Pearl Harbor to seize Australia's New Guinea Territories".

It has also been suggested that Australia was not under grave threat from Japanese military aggression in 1942 and that nothing occurred in 1942 that could justify the description Battle for Australia. These suggestions have not been supported by reference to recognised historical authority, and it appears that those who made these suggestions have either not read (or understood) the official Japanese history of the Pacific War Senshi Sosho (see quote above under chapter title), or the published research by leading Japan scholars and historians, such as Professor Henry Frei and Professor John J. Stephan. A detailed refutation of these suggestions by reference to historical authority can be found in the chapters commencing "The Japanese planned to compel Australia's surrender in 1942".

REFERENCES

Bullard, Steve: see Senshi Sosho below.

Frank, Richard B., "Guadalcanal" (1990) Random House.

Frei, Henry P., "Japan's Southward

Advance and Australia" (1991) Melbourne

University Press.

Senshi Sosho, the 102 volume official history of Japan's involvement in World War II, "Army operations in the South Pacific area: Papua campaigns, 1942–1943", translated by Dr Steve Bullard.

Note: Dr Bullard is a Senior Historian at the Australian War Memorial. The translated text of the relevant parts of Senshi Sosho that deal with Japan's hostile plans for Australia in 1942, including the Japanese master plan Operation FS, is available on the web-site of the Australian War Memorial. The translated text can be downloaded as a page numbered PDF file.

Stephan, Professor John J., "Hawaii under the Rising Sun- Japan's Plans for Conquest after Pearl Harbor" (1984), Univ. of Hawaii.

Wilson, S. "Aircraft of WWII" (1998) Aerospace Publications.

NOTES

1. Bullard translation p.69

2. Frei, chapter "To Invade or not to Invade Australia" pp.160-174, and espec. at p. 172

3. Frei, at p. 172

4. Frank, at p. 19

5. Frank at p. 21

6. Frank, at pp. 21-22

7. Frei, at p. 162-164

8. Frei, at pp. 166-167

9. Frei, at p. 167, quoting views of Chief of Army General Staff General Sugiyama Hajime, also known as "Sugiyama Gen":

"Two days after the fall of Singapore, Army General Chief of Staff Sugiyama Gen moderated the cantankerous dispute (between middle-level Army and Navy staff officers) on the highest level, as he set forth his views on Australia to Navy General Chief of Staff Nagano Osami. The situation for action in Java looked none too bright, said he. But there was hope, and following the defeat of Java the Japanese forces would be pressed to think about the next military operations. These would certainly include Australia, which stood next in the line of assault as it furnished the biggest United States and British bases from which to launch counter-attacks against Japan. Certainly it was important to have an Australia policy, but, at the same time, they also had to reflect on the immense problem of how to control Australia. What they needed was a comprehensive plan that took into consideration all of the country, 'because if we only take one part of Australia, it will surely develop into a war of attrition. This, in turn, could escalate into total war. Unless there are in-depth plans* that consider the control of the entire continent, it is useless for us to plan for an invasion of only part of Australia. On the other hand, there is no objection to plans to isolate Australia by cutting her lines of communication with the United States.' To this end, plans for invading Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia had great value*, and Sugiyama urged that the navy proceed together with the army in a joint study of this operation along already established plans.* General Sugiyama was referring to Operation FS.

10. Frei, at p. 171

11. Frei, p. 172

12. Senshi Sosho, Bullard translation p.69; Frei, p. 167

13. Frei, p. 167

14. Frei, p. 171

15. Frei, p. 171

16. Frei, p. 171

17. Frei, p. 173; Stephan, pp. 96-97, 100-101, 109, 112-115

18. Bullard, pp. 93, 101

19. Bullard, p. 93

20. Frank , chapter ""Strategy, Command and the Solomons", and espec. p.31

21. Bullard, p. 89

22. Wilson, pp. 128 and 130

23. Bullard, pp. 92-94,

24. Bullard, pp. 94-97

25. Bullard, pp. 98-100

26. Bullard, pp. 99-100

RETURN to Main Index